Railways discontinues ‘colonial uniform’: Evolution of the bandhgala, a ‘made in India’ fashion statement | Explained News

When Union Railways Minister Ashwini Vaishnaw announced that railway staff would no longer have the bandhgala as their uniform, he termed it a colonial relic. The garment, however, was one of the first “Made in India” fashion statements to capture the global imagination.

Often called the “prince suit” or the “prince cut” in common parlance, it originated in the princely state of Jodhpur in Rajasthan.

“The bandhgala jacket has always been a court garment of Indian provenance and has evolved from centuries of formal attire in royal India. The buttoned-up jacket with a stand-up collar, however, had varying colonial trappings and embellishments. There were fabric loops or epaulettes on the shoulders for embroidered insignia indicating the wearer’s rank. Sometimes the insignia was pinned on to the high, closed collar itself. The trims, cummerbunds and external paraphernalia may have been colonial but the jacket itself was wholly Indian in origin,” says fashion designer Raghavendra Singh Rathore, who has descended from the line of Rao Jodha, the 15th-century founder of Jodhpur. He is the cousin of Maharaja Gaj Singh II and has resurrected the Jodhpuri bandhgala jacket of his forefathers for modern use.

The Mughal-Rajput blend

The Bandhgala jacket, also known internationally as the Jodhpuri jacket, is not a derivative garment but the culmination of over four centuries of evolution shaped by Mughal ceremonial codes, Rajput warrior aesthetics and the tailoring traditions of Marwar.

“The earliest structural ancestor of the bandhgala appears in the Mughal era jama and angrakha. The jama was the formal court coat of the Mughal emperors, constructed with a fitted bodice, closed neckline, side fastening and flared skirt. It represented imperial authority and was worn in the durbar, diplomatic assemblies and ceremonial occasions,” Rathore says. “Under Akbar, these were refined into highly structured forms with fitted bodices, shaped shoulders and formal closures. The angrakha emerged as a sophisticated variation with a banded neckline, centre-front fastening, fitted torso, shaped sleeves and padded construction.”

When the Rathore rulers of Marwar entered imperial service under the Mughals, the Mughal style court dress merged with Rajput warrior culture. “From the reign of Raja Udai Singh onward, the rulers of Jodhpur adopted a refined court tunic known as the bago. Over time, the Marwar court introduced over-garments such as the dagali and gudadi — structured, padded court jackets worn over the bago for ceremonial and winter use. These garments shortened the long Mughal coat into a true jacket form,” says Rathore.

Story continues below this ad

How polo inspired the modern bandhgala

By the late Mughal period, waist-length fitted jackets were common in court settings, worn by musicians, guards and ceremonial attendants. “The achkan — a close-fitting, high-necked coat, usually reaching the knee and flaring slightly below the waist — during this time is the direct visual precursor of the modern bandhgala. However, achkan was not adaptable for polo and had to be modified to go with riding breeches. It needed crisper jackets, which is why the Jodhpur royals took it to London to style it into a more functional manner for riding,” says Rathore.

The combined outfit of jacket and breeches was called jodhpurs and caught the fancy of the West as Jodhpur polo teams travelled for matches, including to London in the 1930s.

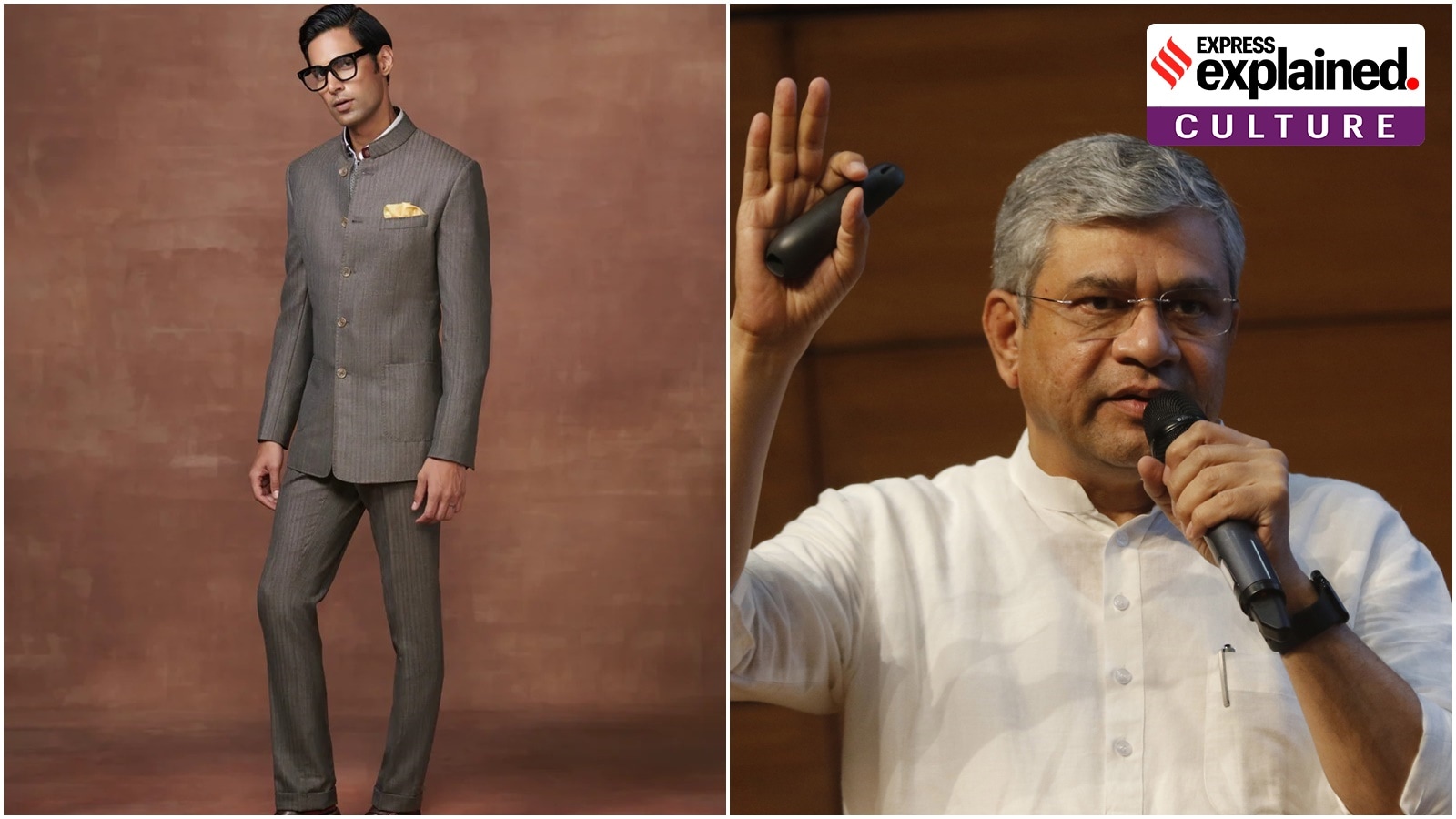

A model in a bandhgala jacket (Credits – Raghavendra Singh Rathore)

A model in a bandhgala jacket (Credits – Raghavendra Singh Rathore)

“In the 19th century, as Indian royalty engaged with European courts and British military culture, this jacket became more popular through a series of royal portraits taken at photographic studios that became an inspiration for the West,” says Rathore.

Of course, there are anecdotal stories of how Maharaja Pratap Singh had lost his baggage of ceremonial wear while attending Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in London and had his kind of outfit tailored on Savile Row.

Story continues below this ad

But Rathore said it was the photographs from India that sparked the tailor’s curiosity about the Indian garment. “Known for their bespoke craftsmanship, they retained the Indian styling of high collar and teamed it up with breeches or riding pants. But they gave it structure, fit and finish with shoulder pads, set-in sleeves that follow the body’s natural shape and precise measurements. The Marwar school of tailoring absorbed new construction techniques. The traditional closed-neck court jacket was refined into a sharply cut, impeccably proportioned ceremonial coat. Thus emerged the distilled bandhgala as we know it today,” says Rathore.

Since Maharaja Umaid Singh was an aviator and set up the Jodhpur Flying Club in 1930, he had an American squadron stationed in Jodhpur. “They popularised the Jodhpur boots, breeches and also the bandhgala,” says Rathore.

The politics of functionality

The high-neck jacket, according to Rathore, was designed for functional reasons. “It was to beat the cold of north India in the absence of scarves and ties. You don’t find such collars in southern kingdoms from the same period. Also, the royals could show their precious stone-studded jewellery to great effect with the bandhgala,” he adds.

The English had other reasons to popularise the jodhpurs. “One, high collars were also in use in China and Japan, with which Britain had trade. So, it attempted to build a pan-Asian cultural sameness. In India, they made a strategic concession to this cultural motif under the veneer of assimilation while creating its own administrative elite through English education and Western sciences. In their bid to homogenise Asia, they imbibed bits of local culture and made them part of English styling as a visible show of cultural accommodation,” says Rathore.

Story continues below this ad

Rathore reprised the bandhgala while studying in New York and sparked the interest of Donna Karan and Oscar De La Renta. “I did the elevated cuts in 1994 and these became popular once I dressed up actor Saif Ali Khan in Eklavya,” he says.

link