Barbara Hulanicki on breaking rules and revolutionising fashion

Emmanuel Lafont

Emmanuel LafontIn the 1960s, Barbara Hulanicki disrupted the stuffy, class-ridden view of fashion, and the inclusive Biba lifestyle changed everything. She talks to the BBC about her extraordinary career.

“Biba attracted troublemakers or people who liked to make trouble,” asserts Barbara Hulanicki, the ever-energetic founder of the legendary British 1960s and 70s label and four boutiques, now aged 87. Her cutting-edge retail ventures culminated in its largest, final incarnation, the seven-storey Big Biba, which occupied the former Art Deco Derry & Toms department store on London’s Kensington Hight Street. The latter offered fashion, homeware, a food hall, beauty salon, 500-seat restaurant in the top-floor Rainbow Room, and roof terrace with a garden, flamingos and errant penguins (some were once found waddling down into the store). Big Biba was the highpoint of a trailblazing career that saw Hulanicki disrupt a class-ridden, stuffy view of fashion, and usher in a more fun-loving, youthful, affordable and egalitarian approach to dressing.

Tessa Hallmann

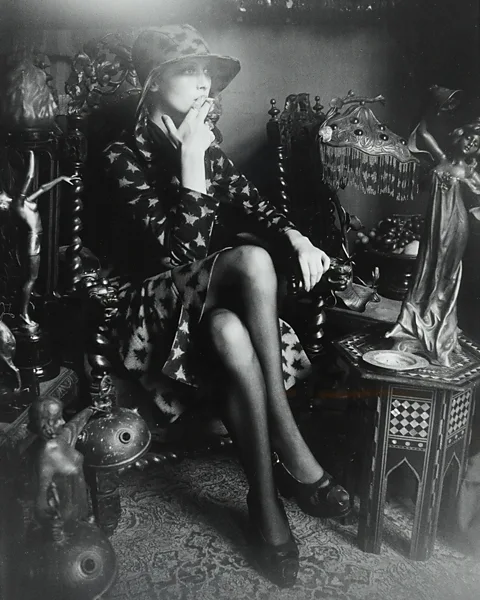

Tessa HallmannBiba’s aesthetic might seem retrograde – especially in the forward-looking 1960s context of futuristic, space-age fashion and design. But Hulanicki counterintuitively grasped the nascent appeal of Edwardiana and Victoriana and, later, Art Deco, all poised to enjoy huge revivals. Biba’s early shop interiors – the original one occupied an old chemist on Abingdon Road, Kensington and opened in 1964 – channelled fin-de-siècle exoticism.

Hulanicki worked closely with creative people who shared her mindset. Designer Julie Hodges designed Orientalist wallpaper with large-scale motifs in opulent shades like rose madder gold. The shops were furnished with bentwood coat stands and chairs whose curlicues echoed the sinuous lines of the sumptuous black-on-old-gold graphics and logos dreamt up for Biba by Antony Little (co-founder of Osborne and Little) in the mid-1960s. “Bordello” and “souk” were descriptions Hulanicki and others bandied about to describe the boutiques’ interiors, where customers not only scrambled to buy the latest, low-priced garments but were also invited to lounge on their window seats or floor-level velvet cushions.

Barbara Hulanicki Archive

Barbara Hulanicki ArchiveOn the fashion front, publicity shots pictured winsome models, faces framed by bubble curls and turbans, throats adorned by chokers; Hulanicki’s gouache or watercolour fashion illustrations for Biba pictured willowy, sooty-eyed women with frizzy hairdos reminiscent of Gustav KIimt paintings of bohemian beauties. By 1970, 1930s old Hollywood began to be its principle inspiration. Nineteen-twenties-style cloche hats and feather boas had long hung casually from the boutiques’ coat stands but, increasingly, elaborate publicity photographs showed models, notably Twiggy, languorously reclining in liquescent satin, ankle-length, bias-cut dresses paired with towering 1930s-style platforms. The latter look was vampish – a Biba leitmotif was leopard print stamped on clothes and homeware.

Yet Biba was forward-looking socially: it effortlessly espoused and promoted progressive values and a permissive spirit that helped accelerate the snowballing radical social changes of the day, such as feminism, gay liberation and black civil rights. When, in 1971 the far-left anti-capitalist terrorist group, The Angry Brigade, detonated a bomb in the third Biba boutique – on Kensington High Street – in protest against women’s enslavement to fashion, they were missing the point. Biba’s ethos was playful, offering customers a pluralist dressing-up box of looks that consciously interwove high style (on a budget) with kitsch, while not idolising consumerism. For Hulanicki, who co-founded Biba with her husband Stephen Fitz-Simon, who ran the business side, offering an enjoyable haven for rebels was more important than turning a tidy profit.

Barbara Hulanicki Archive

Barbara Hulanicki Archive“There was so much money going through the tills – every hour, someone would take the money out and give it to Fitz,” recalls Hulanicki, who was born in Warsaw to Polish parents. “One day, a shop assistant accidentally gave a customer a bag of money instead of the carrier bag of clothes she had bought.” Shoplifting was rife but was seen as a useful indication of the success (or failure) of a new garment or collection: “Everyone was welcome to be part of our community. I’d think: ‘Help yourselves! If you like it, steal! When new stock came in, I’d ask the shop girls: ‘How is it selling?’. They’d often say, ‘Yes, it’s going well, we’ve had at least three pieces stolen.’ That was proof that a garment was a winner.”

Biba continues to exert a fascination both among its original customers and today’s young fashion buffs – testament to its lasting appeal. London’s Fashion and Textile Museum recently mounted the exhibition, The Biba Story: 1964-1975, which notched up record-breaking visitor numbers – it showed how Biba “changed the way people shopped”. It’s set to tour in Edinburgh and Miami, where Hulanicki moved to in the mid-1980s, establishing a new career as an interior designer. And, to mark the 60th anniversary of the opening of the first Biba boutique, a new book co-written by the show’s curator, Martin Pel, and Hulanicki – Biba: The Fashion Brand that Defined a Generation – has just been published. And London-based Kerry Taylor Auctions recently held a week-long online exhibition and auction of Biba clothes, accessories and ephemera.

Tessa Hallmann

Tessa HallmannA number of tomes have chronicled Biba’s 11-year history over the decades, so, for Hulanicki, what is the difference between these and the new book? “I love this one as it’s all insiders’ views of Biba,” The book features reminiscences of store managers, buyers and models. “We hired people we knew were going to be a character and weren’t snooty. People, mainly women, who understand what was going on. People were proud of being part of Biba: they weren’t just slaves or cogs in an organisation.” In the offices of Biba, a large bottle of Guerlain’s Mitsouko perfume was there for staff to spritz themselves with.

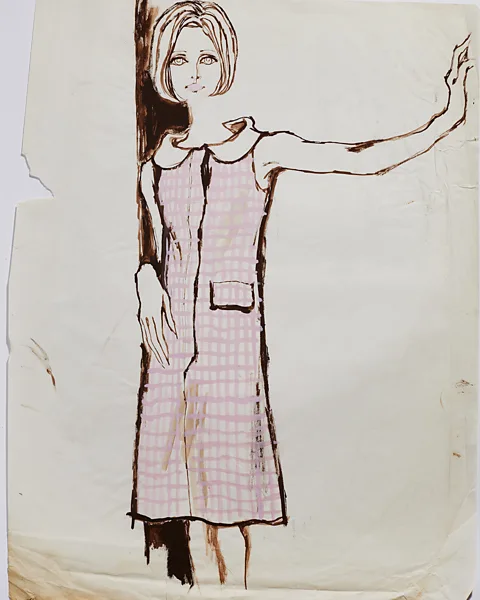

Hulanicki rebelled against the fashion system as it stood when she first entered the profession as a fashion illustrator in the 1950s, having studied fashion and art at Brighton Art School. She then worked as any accomplished fashion illustrator for Vogue and Women’s Wear Daily, but she regards this work as stiff and too formal – emblematic of an anachronistic society.

‘A revolt in fashion‘

A major turning point was her creation of a comparatively understated gingham dress and matching headscarf commissioned by Felicity Green, fashion editor of The Daily Mirror. The simple, jauntily checked outfit – inspired by Brigitte Bardot’s 1950s get-ups in Saint Tropez – was a smash hit: 17,000 outfits were ordered.

Hulanicki’s Aunt Sophie greatly influenced Biba’s aesthetic, although Hulanicki says she had a “love-hate” relationship with her domineering aunt, who adhered to outmoded social rituals. Yet, inadvertently, her clothes made of delicate, luxurious materials, such as crepe de chine in dusty shades not seen since the 1930s, inspired much of Biba’s clothing. “When we stayed with her, she would have you change throughout the day – wear something different for lunchtime, teatime, drinks time, dinner time.”

More seriously, Aunt Sophie was censorious – a common insult towards young women in the 1950s and 1960s was to call them “sluts”, Hulanicki recalls, if they did so much as peroxide part of their fringe. (Interestingly, Hulanicki’s trademark look in the late 1960s was a sharply geometric platinum bob, outsized shades and a leopard-print jacket reminiscent of 1940s Hollywood.) One reason why Biba constituted what Hulanicki describes “a revolt in fashion” was that its young customers had, in her view, suffered “tough mental treatment at home from their mothers”. “Just after the war, their dads weren’t there, and many mums felt they had to impose the same discipline on their daughters that fathers would normally have done.”

Barbara Hulanicki’s five Culture Shifters

Audrey Hepburn in Sabrina (1954) She’s always been a huge heroine of mine, with her fresh, personal take on make-up and simple pearl earrings. I once walked into a lift with her, which was terrifying, but she was very natural and friendly.

Ready Steady Go! (1963-1966) The pop and rock TV show which was totally on Biba’s wavelength. Its presenter, Cathy McGowan, like Cilla Black who was often on it, too, often wore Biba clothes. I love the fact that Elton John worked there for a while, making everyone coffees.

David Bowie on the cover of album Diamond Dogs (1974) He used to wear our men’s make-up range and regularly dropped into Big Biba.

No Orchids for Miss Blandish (1939) A crime novel by James Hadley Chase. I read it at the public school where my Aunt Sophie sent me to learn to be a nice girl. But the book is very racy, and made entertaining reading.

The Marlin hotel by Island Outpost (1991) Music producer Chris Blackwell was one of the first people to open boutique hotels, and the first to do so in Miami. I designed the interior. The Marlin was seen as the fire that reignited Miami as a fashionable, cool resort rather than a place where people go to die.

Biba’s success largely rested on Hulanicki subjectively basing its aesthetic and philosophy on her taste – in theory, a risky strategy. Yet her vision struck a chord with an entire generation. These numbered not just Brits but Europeans. “It was exciting that many of our customers flocked to the stores from Paris – they made pilgrimages to Biba.”

Biba’s cosmetics range, first launched in 1970 and incorporating such challenging but surprisingly coveted hues as vampish, artificial chocolate brown and prune (that channelled the look of old Hollywood’s silent-movie stars) or very pop, artificial royal blue and green – all designed to coordinate with Biba clothes – sold internationally. Customers could try the make-up on in the stores (unheard of anywhere else). “There was a camaraderie among customers trying on the make-up – something they could all afford.”

Barbara Hulanicki Archive

Barbara Hulanicki ArchiveThe make-up didn’t just have a skin-deep appeal. The chromatic variety it offered – greatly broadening the narrow conventional range of pale pinks and ivories on offer elsewhere – reflected deeper social change. Biba launched the first full range of make-up for black skin. Like many of Biba’s new ranges, this was developed by observing and interacting with customers, says Hulanicki: “The make-up for black skin was inspired by Jamaican girls who came into the second shop and were seeking colours that suited them. They’d come in with their mums who were looking after them – and often joined in. Biba was inclusive, classless, and not just because of its price points.” Biba also offered a make-up range for men, which dovetailed with the prevailing androgyny of glam rock. Within three years of its launch in 1970, Biba make-up was selling in 30 countries across three continents. The famously androgynous David Bowie was a regular visitor to Big Biba: the new book includes a photograph of him at a party there. Groundbreaking bands, from the New York Dolls to the Pointer Sisters, performed at Big Biba’s Rainbow Room.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBiba’s all-encompassing vision wasn’t pre-calculated but developed organically, insists Hulanicki. “Over the years, the Biba customer had grown up, and the company grew with them. She moved on from the 1960s, mini-skirted dollybird look to a more sophisticated style catered for by our 1930s-inspired styles, but they were also buying their own homes, and this was reflected by Big Biba’s many departments catering also to homeware, menswear and, following the birth of our son, Witold, named after my father, children’s wear too.” Big Biba’s comprehensive lifestyle concept of Biba-branded products has influenced many other retailers since Biba’s demise, from Anthropologie to Zara and Zara Home. It helped change how people shopped – and how people thought.

Biba: The Fashion Brand that Defined a Generation by Barbara Hulanicki and Martin Pel (Yale University Press) is out now in the UK and from 5 November in the US

link